In the 1950s, smallpox was still killing two million people a year. But after centuries of suffering from what vaccination pioneer Edward Jenner called “the most dreadful scourge of the human species” a global cooperative effort starting in the 1960s helped effectively eradicate smallpox from the world.

This precedent – the idea that when working together the world can solve great, global problems, underlies the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). With a target date of 2030, they cover 17 different goals (see our infographic below). Underneath these goals sit a further 169 targets and 232 individual indicators.

The SDGs build on and supersede the UN’s Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), an attempt to align development initiatives and interventions in the developing world.

The MDGs were:

- eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

- achieve universal primary education

- promote gender equality and empower women

- reduce child mortality

- improve maternal health

- combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases

- ensure environmental sustainability

- global partnerships for development.

Whilst the MDGs were focused on the developing world, the SGDs are truly global – and that’s a crucial difference.

Why SDGs matter

Why do SDGs matter? First, they allow for a concentration of effort, a globalisation of good. By aligning programs or organisational activity towards a specific set of goals, an NFP can focus its efforts in the same area as thousands of organisations around the globe. Whether the goal is Zero Hunger, or Peace or Innovation and Infrastructure, there are massive economies of scale in having multiple organisations pushing towards the same outcome.

To take the ‘economics’ of SDG-aligned goals even further, having many thousands of organisations around the world working towards the same goals – but in different locations, with different resources and approaches – allows for vast differentiation, experimentation, innovation and improvement, at a time when it’s easier than ever for organisations to share their methods, IP and results.

Similarly, SDGs give organisations the ability to place their specific, local programs and projects within a larger national and global context and link the work they are doing to global outcomes. As a result, NFPs can engage donors on their local issues – because their performance can be seen in a global context using a shared ‘vocabulary’.

In a global context SDGs have now moved beyond being just goals. “We’ve met some really great organisations that have the SDGs embedded into their strategy and mission, internal and external communications and marketing plans,” says Emily Wellard-Baring, Senior Philanthropy & Non Profit Services Manager at Perpetual. “This is much rarer in the Australian context, but there are organisations moving in that direction.”

The UN, major global funding bodies and major country aid institutions now use the SDGs to guide their aid funding and programming decisions. So do most Australian development agencies working internationally. But many Australian NFPs do not align their activities to the SDGs. Let’s explore how we know that, why it matters - and what can be done to change it.

Are Australian NFPs aligned to the SDGs?

Each year, Perpetual invites not-for-profit organisations to apply for funding through our IMPACT Philanthropy Application Program or IPAP for short (in FY20 we committed over $24 million in funding via IPAP). Over 1,000 organisations applied in FY20 and as part of that process we asked them to identify up to three SDGs their organisation – or the project they were seeking funding for – were aligned to.

Our analysis of these results (which were collected in October-December 2019) came up with some interesting insights.

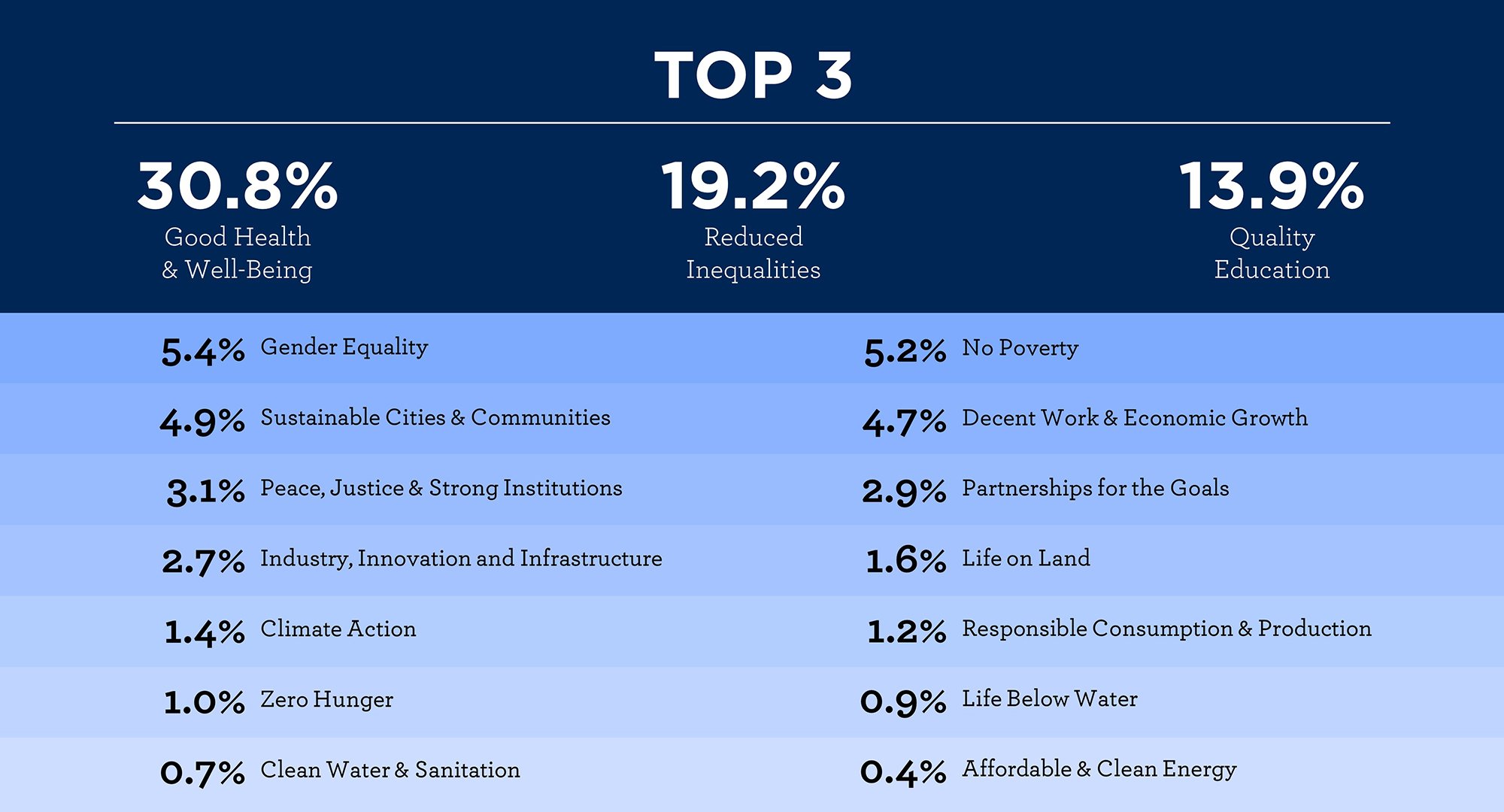

In FY20, only three SDGs were seen as relevant by more than 10% of IPAP applicants.

In FY20, only three SDGs were seen as relevant by more than 10% of IPAP applicants.NFPs and SDGs – some big goals, some big misses

Three SDGs were seen as relevant by significant numbers of the NFPs applying to IPAP. They were:

- Good Health and Well-being (30.8%)

- Reduced Inequalities (19.2%)

- Quality Education (13.9%)

Indeed, these three goals dominated the results, leaving goals including Life Below Water, Clean Water and Sanitation and Affordable and Clean Energy with relevance scores of less than 1%.

A toxic environment

Interestingly, environmental issues rated very lowly. NFP programs were aligned against Climate Action in only 1.4% of applications and Affordable and Clean energy in only 0.4% of applications. In total, only 3% of IPAP funding was directed to environmental causes.

Amanda Martin of the Australian Environmental Grantmakers Network (AEGN) says this mirrors some aspects of the broader landscape. “Only a small proportion of charities in Australia are environmental charities – according to the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission they made up just 0.02% of all charities that submitted returns. Most of these organisations are small. Just 41 environment-focused charities generate over $1 million in funding each year, so a few players are doing most of the heavy lifting.”

Amanda is hopeful that the greater sensitivity to the environment brought about by the 2019/2020 bushfires will improve these numbers. But she also believes the entire charitable sector has work to do.

“Given the scale and complexity of the environmental crisis we find ourselves in, we need the entire charitable sector to consider environmental SDGs.”

Amanda Martin, Australian Environmental Grantmakers Network

“Given the scale and complexity of the environmental crisis we find ourselves in, we need the entire charitable sector to consider environmental SDGs, which can help organisations to focus their strategy and guide where work is needed and where money should go.”

Amanda also says the issue goes beyond just the environment groups. “There’s increasing recognition across other funding areas, from health to education to food security, that environmental issues are inextricably linked. Climate change, for example, is recognised by the World Health Organization as the single largest threat to health, yet in Australia the amount of philanthropic resources dedicated to the issue is small. We need an environment lens applied to all charitable and philanthropic work in the same way we apply the gender lens”. On that note, the AEGN is working on a climate change lens for philanthropy due early next year.

The gender issue

Gender Equality ranked as the fourth most nominated SDG in Perpetual’s IPAP data (in 5.3% of applications). Julie Reilly of the Australian Women Donors Network says the SDGs have a vital role to play in the battle for gender equality. “The SDGs are about recognising common problems and committing to common actions. The UN itself points out that gender equality plays a key role in the achievement of the other 16 goals – it’s a crucial part of the SDG strategy.”

“The SDGs are about recognising common problems and committing to common actions. The UN itself points out that gender equality plays a key role in the achievement of the other 16 goals.”

Julie Reilly, Australian Women Donor’s Network

In IPAP applications, Perpetual asks NFPs whether they’ve run a gender analysis. Encouragingly, over 85% of applicants who selected ‘Gender Equality’ as a relevant SDG said they’d run a gender analysis of their program.

Julie says, “For NFPs, it’s doubly important, because a gender lens is about ensuring women are well served and also because funders will be asking them to demonstrate a gender impact analysis to show they actually understand the gender issue.”

But Julie says gender analysis should be a hygiene factor for all NFPs. “It’s an old example – but a good one,” she says, “Until 2012, an Australian woman in a car crash was 47% more likely to suffer serious injury. Why? Because the cars’ safety systems were built using ‘male’ crash test dummies. That’s a metaphor for how we look at all sorts of issues – including a post-COVID recovery. If you don’t think about the gender lens – the high proportion of women in healthcare, and COVID-affected areas like retail and tourism – then how can you fashion an effective response, whether you’re a charity or a government agency?”

Local vs global

One other key finding from our IPAP data was that organisations with a global focus were far more attuned to the benefits of aligning programs to the SDGs. This may reflect the fact that international development funders (including Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade) expect SDG alignment and use this to direct large scale funding. By contrast, the vast majority of domestically focused NFPs with a social welfare focus are receiving funding from local, state and even federal government agencies and domestically focused funders that were much less likely to focus on alignment to SDGs.

The bigger picture

Organisations that put SDGs at the centre of their approach are part of a greater whole. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade has committed to reporting Australia’s progress in pursuing the SDGs – and to report not just on government involvement but across the whole economy.

This support from government highlights, paradoxically, that achieving the SDGs is not about governments. And it’s not just about NFPs. In many ways they are whole-of-society targets that should be core to the thinking of all the moving parts of civil society – government, business, NFPs and philanthropists.